CLD driven storytelling

The capabilities and features of digital platforms for visual storytelling and interactivity are highly suitable to communicate and disentangle a CLD's complexity.

A story, such as resource scarcity and connected social issues in the Omo-Turkana-Basin, includes a variety of stakeholders,

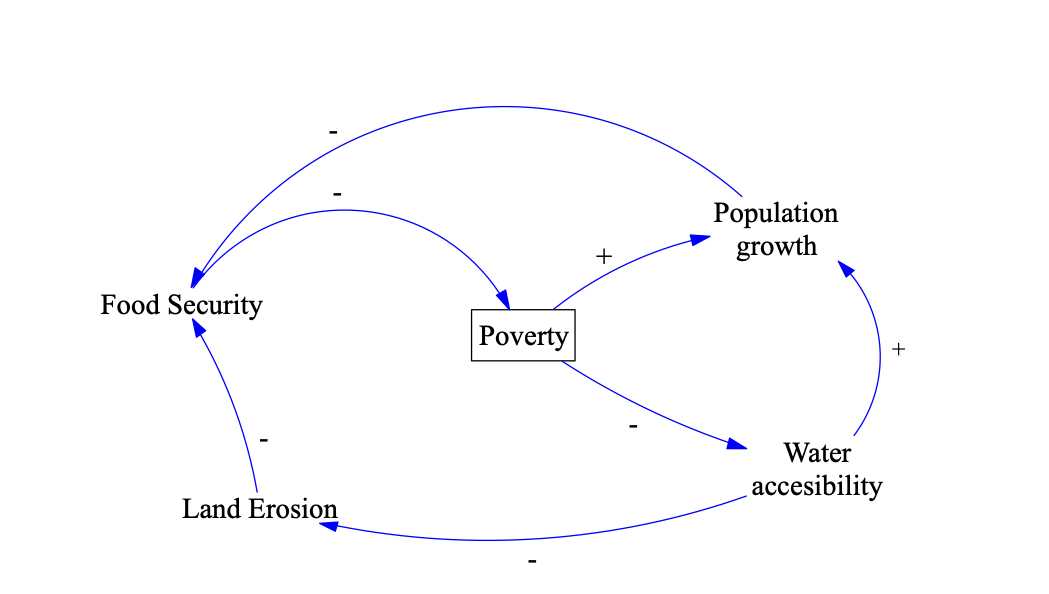

with different interests far beyond what has been scribed here. Overall, the research's resulting aggregated causal loop diagram held more than 80 variables. In text-form, the entailed complexity would be almost impossible to reasonably communicate to a reader.

During research on the DAFNE project, we experienced the intuitive nature of CLDs in communicating research results and problem structures.

Why not exploit the capabilities of CLDs, expand, using the capabilities of web visualization and interactivity, and tell stories?

Expand the box below to see how we imagine this in practice.

Principles for communicating CLDs

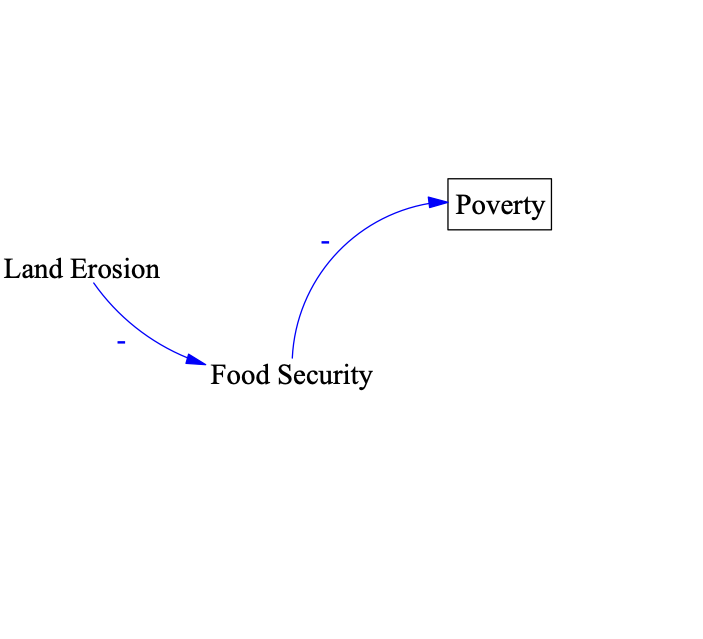

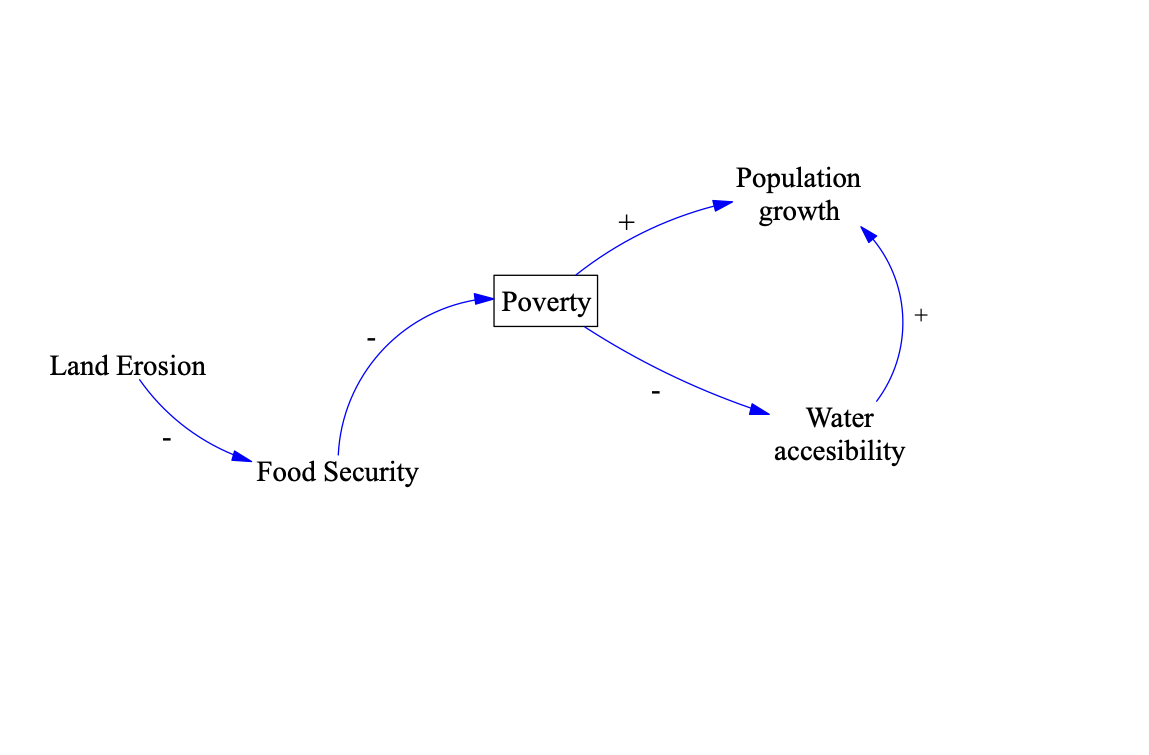

Stepwise storytelling

The final, complex network-structure displayed by a CLD does not just appear out of the abyss. Closer to reality, a CLD is developed within an iterative process of adding variables and links step by step. Similarly, a CLD should be communicated. Start with the central variable and explain the involved complexity step by step by including more variables. Don´t confront the reader with the full picture at the very beginning. A dynamic unfolding of the CLD, as depicted in the animation above, is more meaningful to understand the story behind the nodes and links.

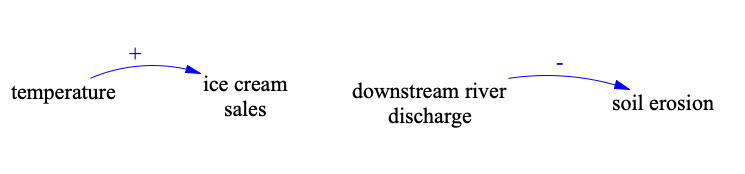

Links are more than binary

Even though the CLD simplifies causal relationships to a binary level, that should not limit the storytelling to the same level. Some links might hold insecurities, ambiguities, or disagreement. Thus, provide further information for links. Use them as interactive items to display further information as the reader clicks on them.

Disagreement to the front

An essential part of participatory modeling is the integration of diverse perspectives. Diverse, and probably disagreeing perspectives need to find a special place in the storytelling. One of the strengths of participatory modeling is to systematically map disagreement of stakeholders concerning the messy problem in place. This comes to hold relevance in the aggregated CLD which points differences out explicitly. For storytelling, the aggregated model can be used to highlight disagreement. The network structure than allows a reader to quickly assess the consequences.

System Dynamics

The simple CLD structure allows creating drawbacks to the overall behavior of a system. In which direction is it heading, what are the key reasons for, and what are its consequences? Good CLD-driven storytelling communicates these insights and makes them highly visible.

Interactivity and additonal information

The advantages of digital platforms allow high levels of interactivity features for the reader to investigate the CLDs by herself.

Web-developer?

We are soon starting development on an open-source web-framework to enable CLD-driven storytelling. If you want to support the development and are capable of web-development please get in touch with us. Within this project, we would like to enable all the principles described above to enable high-quality storytelling.