The Challenges and Opportunities Digital Technologies Bring to Journalism

The question of how people get the news has never been more relevant. Not only we have bypassed the television/radio/newspaper triangle that dominated most of the 20th century, but the complexity of digital technologies now requires us to find new ways to generate an answer to that question.

Without doing too much of a history lesson, it is useful to provide a picture of the major changes news media organizations have undergone in the last few decades, the result of the increased dominance of digital technologies as a communication medium. To begin with, newsrooms across the globe have seen their online-base growing in relevance, indicating a shift in readership from print towards digital. Second, journalists themselves are increasingly more reliant on digital technologies to source their news, which happens on a couple of levels. On the one hand, the shift in the audience from passive to active, as captured by Rosen’s famous description of “the people formerly known as the audience”, has changed the degree of control of the conversation hold by the media. Not just the younger, but also older generations are now starting to get their news through social media. Social media embedded news is constituted of what their network connections share, what their personalized news feeds shows them, and what their followed celebrities, preferred news organizations, and influencers choose to discuss.

Also, individuals are increasingly important in turning something newsworthy through the act of resharing, making the topic societally relevant. What social scientists call peer-to-peer diffusion, the resharing among network connections can sometimes take on such a fast and continuous spreading pace as to resemble a viral contagion. This phenomenon is what lies behind the emergence of viral content, and in a digital world with near infinite conversations, personalities, and publications, virality is something the media ecosystem is slowly learning to familiarize itself with, as the battle for the audience attention becomes increasingly harder.

It appears thus that journalists are facing some tough challenges as the result of the digitization of our lives. And for a big part, that is true. Polarization, the spread of misinformation and “malinformation”, the struggle to control the conversation, loss of trust in official media sources by a section of the public, the constant monitoring of social media ecosystems, and understanding the complexity of news emergence and diffusion in social media networks in the attempt to adapt to changes in society, are all real challenges the media ecosystem is facing today.

It would be unfair, however, to neglect the positives that the digital realm has brought to journalists. News gathering now happens at a much faster pace than before. News sources can be verified in just a matter of seconds, making news more timely, transparent, and reliable. Reaching audiences is also now somewhat easier. Content is out there for everyone to see, while before it was only the already-engaged readership that was likely to expose itself to such content. Additionally, the flexibility for readers to digest news content at their preferred time makes the job of reaching audiences somewhat easier. These are some examples that highlight that digital technologies bring opportunities, along challenges, for journalism.

Tackling Digital Marginalization

As mentioned above, one challenge journalism is facing today is that of capturing an audience’s attention. The supply of entertainment sources is greater than ever, making the task of retaining an audience really difficult. It is no surprise that most news media organization have seen their audiences shrink in the last decade, as individuals, and particularly young people, prefer to get their news from social media apps, and often not from news media providers, but rather by influencers and through social popularity clues such as hashtags and trending signals. At the same time, the type of content that often trends of social media is that of a different nature from the one released by news organizations – think of memes, Buzzfeed-like kitten videos, and viral contests. News media organizations’ competition for attention is thus with a content-type that differs substantially in both tone and nature, from that it, in some ways, has the duty to report. Battling against online marginalization, newsrooms have to a certain extent tried to adapt to audience preferences through an editorial restructuring. The type of stories we see them publishing in their online platforms are considerably more positive in nature, opinion-based and cultural-embedded, than the stories that used to dominate their print publications. Some questions arise when news media organizations have to transform themselves to stay afloat. Do these changes impact the definition of news? Do they impact the quality of information and the depth of collective knowledge? As Neil Postman famously stated a few decades ago, are we drowning in a sea of irrelevance and amusing ourselves to death? To what extent should the public determine what is newsworthy? And what is the role of journalism, ultimately?

Nowadays traditional media organizations are accompanied, in the online realm, by new emerging media companies, like Buzzfeed, Upworthy, Mashable and The Huffington Post, which are born out of the digital, and that, contrasting with news websites, generate content aimed at going viral, instead of reporting news in accordance to some news value indicator. There are lessons to be learned from such companies. Their dedication to learn and master the science of virality, how to make people reshare their content, and ultimately, grab online audience attention, can have important insights for news organizations. And as news media organizations tweak their headlines, their editorial choices, and choice of formats for their stories, one critical task is that of being able to assess the outcome of these choices in successfully spreading content better in the online, compared to i) themselves in the past; ii) these emerging media companies. As we make the case for in this article, one such tool, able to accomplish that task in a scientifically-grounded manner, is diffusion modeling.

Diffusion Theory and Modeling

Originating in the ‘60s, the sociological theory of diffusion exists to assess how things like innovations, products, rumors, or even news, spread in a society. Within the realm of academic studies of journalism, diffusion theory has served to assess various aspects of news spread ranging from measuring the speed of spread of one news story across a population (Greenberg 1964; Kanhian and Gale 2003), the role of different channels in the news diffusion (Rogers 2000), the life course and development of news (Rogers 2000; Im et al 2010), the characteristics of the audience (Ihm and Kim 2018), or of the news in itself (e.g. the content type) (Inoue and Kawakami 2004), and the relationship between the news and the audience (e.g. personal relevance) (Kanhian and Gale 2003).

Here, we make the case that newsrooms themselves can avail of measures of diffusion to gain insights on how they are reaching their audience, in how they are performing against competitors, and to test how successful different strategies are in enlarging their audience reach, through an increase of peer-to-peer diffusion (the resharing of content among network-connected individuals). In the section below, we present the technicalities of diffusion modeling, and provide a walk-through tutorial on how to perform diffusion modeling using one’s own company data, but also inferring about a competitors’ performance in content spread.

A Practical Guide

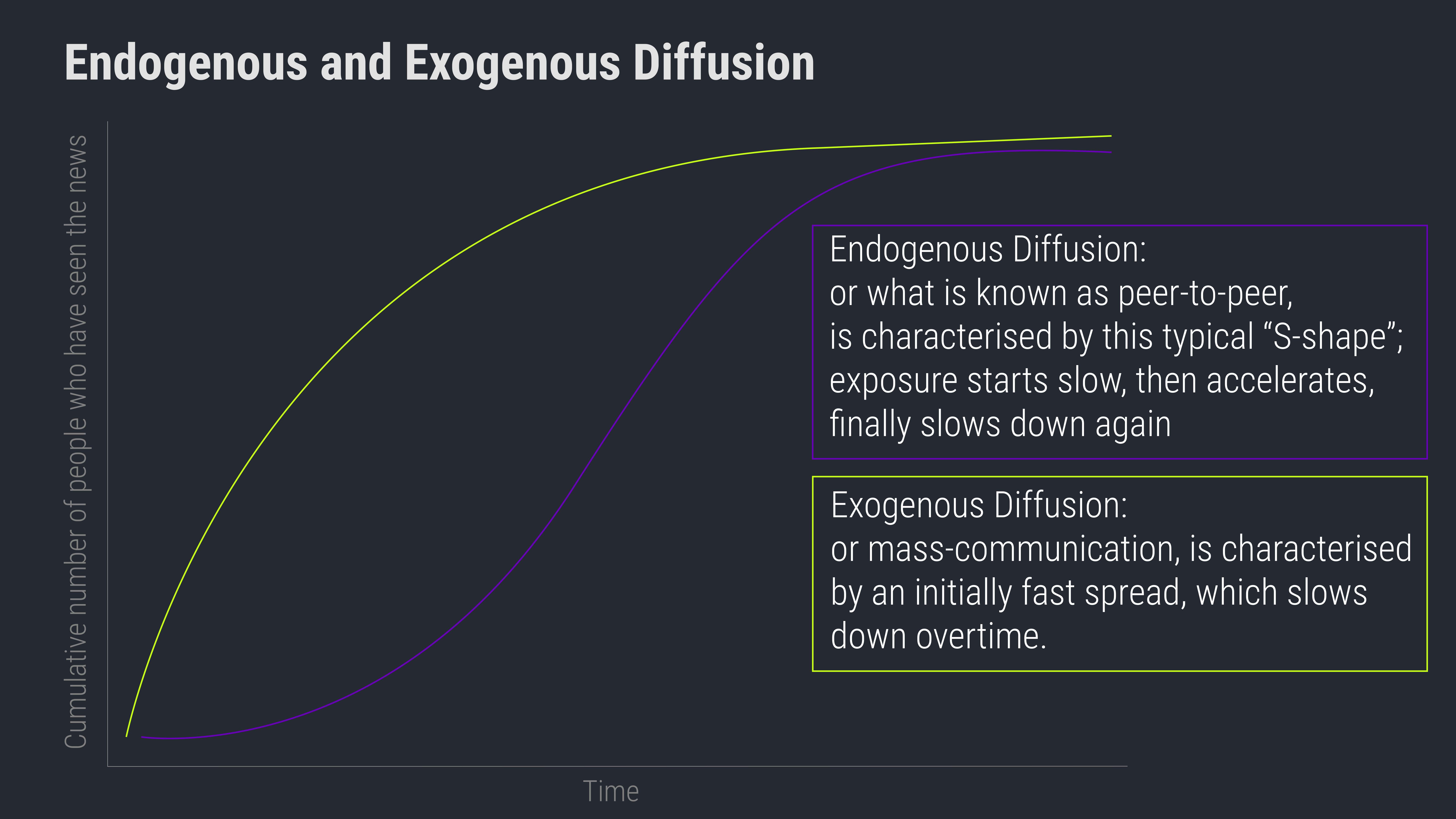

Generally, to measure how something diffuses means to obtain quantitative measures that capture the way the object in question spreads. There are generally two ways things spread in society: exogenously and endogenously.

Exogenous diffusion describes a diffusion process where an external source (e.g. a media organization) imposes a centralized source of influence on the individuals to adopt an innovation. Within this process of external influence, each individual is equally likely to adopt the innovation. Endogenous diffusion is based on internal processes within the social system, among the individuals, that include social interaction e.g. passing of information about an article or publication.

Most often, in the world news spread as a result of both exogenous and endogenous processes. A publication or even an event in itself is first instilled in the digital landscape by a media organization, exposing some “early adopters” to the story. Some of these early adopters might thereafter choose to share the news through their digital social networks, taking a role in the diffusion process of the story. Essentially, to be assessing how news diffuses means to capture the extent to which a news has diffused exogenously and endogenously. This is done through what we have already referred to as diffusion modelling.

sidenote: not all events follow this exogenous first, then endogenous trend. For instance, citizen journalism and generally, social media embedded viral content might otherwise be endogenous at first.

To model diffusion means essentially to represent the news reach process as a function that maps time to the number of individuals who have been exposed to the news (in technical terms, who have “adopted the innovation”). For each time point we have an indication of how many people have reached the news.

To capture both the level of exogenous and endogenous diffusion of a publication, a model known as the Bass Mixed Influence Model can be used. Bass's model is based on the assumption that two forces influence an individual to be exposed to a publication: one’s peers and the mainstream media.

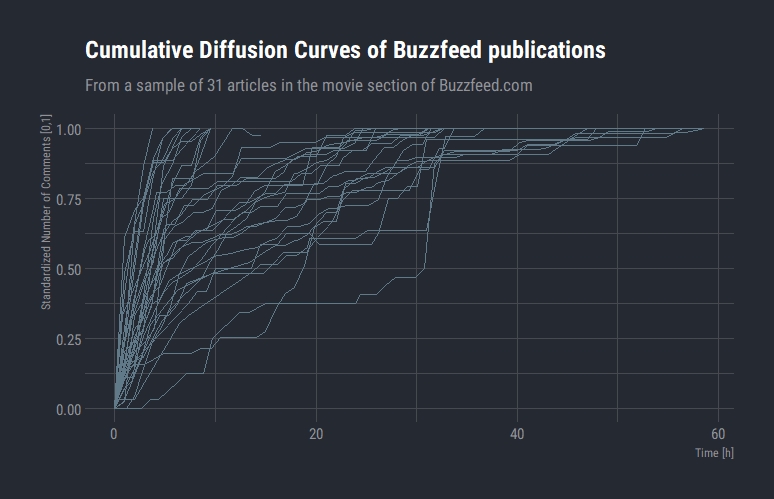

The image here below shows the plotted lifespans of a sample of 31 Buzzfeed articles. For each article, we scraped information about the number of comments, and used that as a proxy for views. We then cumulatively plotted the number of comments overtime. After that, we have retrieved the endogenous and exogenous coefficients for each article using the diffusion package in R. The higher the strength of one coefficient, the more predominant is that diffusion mode for that particular publication.

We have compiled here below a series of core readings on diffusion theory, and some examples of diffusion theory applied to journalism:

- Bass, F. M. (1969). A new product growth for model consumer durables. Management science, 15(5), 215-227.

- Mahajan, V. and Peterson. R. (1985). Models for Innovation Diffusion. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of innovations. Glencoe. Free Press.(1976)," New Product Adoption and Diffusion," Journal of Consumer Research, 2, 290-304.

- Rossman, G. (2014). The Diffusion of the Legitimate and the Diffusion of Legitimacy. Sociological Science, 1, 49.